Masks of Multi-interpretations

by Kuss Indarto

by Kuss IndartoExamining the works of Dyan Anggraini, in my opinion, is like looking at ourselves in the mirror. It is an inward-looking persuasion, a self-introspection. Through her works, we are provoked to observe fragments of reality and its representation that evolved within our daily live. Whether or not we are consciously aware of them, the theme of her works (featuring various figures in masks) is connecting both denotative and connotative meaning of (man in) mask.

Mask is not perceived as “it is”, a cultural (read: art) icon existed in Indonesian ethnics, but rather as a meaning connoted by various system of interpretation or even deconstructed by the changing lexical (and social) values within the context of its culture.

Denotative Mask

At first, mask is a face protector – made from wood, paper, clothe or other – in various form used by traditional dancers of performance art. Several masks may resemble the face of god-goddess, various expressions of human, faces of demons and other beings.

In Bali, for example, mask plays an important role in a traditional theatre-dance performance – in which all players wear masks -- featuring stories known as babad. While performing their roles, dancers wear masks of bungkulan (masks that covers all of the face) and sibakan (masks cover part of face from forehead to jawbone). Those who wear bungkulan do not necessarily converse during the performance, while all characters wearing sibakan will communicate in Kawi (the ancient Javanese language) and Balinese language.

The main characters of the performance consist of Pangelembar (topeng keras and topeng tua), Panasar (Kelihan, older character while Cenikan is the younger character), Ratu (noblemen and official), and Bondres (common people). In Pajegan mask dance, all the characters will be played by one actor including the must perform Sidakarya mask. Due to its proximity toward religious ritual, Pajegan is also known as Wali mask dance. This particular performing art is popular throughout Bali. We could also find Prembon mask dance featuring various characters from Panca mask dance, Arja and Bondres. Prembon mask dance is relatively new for Balinese people emphasizing on its comic characters and their jokes.

Similar condition found in Cirebon, West Java. Mask has been a cultural icon closely related to the local’s art scene and its activities. Interestingly, Cirebonan mask dance is not merely a performance art, but often considered as a religious ritual filled with historical values. It plays an important role as a medium of Moslem preaching in this area done by Sunan Gunung Jati. Therefore, the mask dance has been a key witness of syncretism between Islam and Javanese culture.

Mythical stories are often found surrounding the Cirebonan mask dancer. Take for instance maestro of Cirebonan mask dancer Rasinah, a lively person despite her elderly age, who conduct (40 days) ascetic fasting prior to her performance.

There has been other mask dancing traditions in various areas such as Banyuwangi, Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Banyumas and others. All could be referred as an example of mask’s denotative meaning within the familial aspect of our daily live. Throughout the history, the word mask has been distorted, altered within its changing referential system. Mask or disguise has often signified as a way to cover oneself toward the reality. This is a substantial and key point underlying the works of Dyan Anggraini.

Evolutional Path

Mask has been presented in various aesthetics nuances in Dyan’s canvass, a medium of expression in regards of various social and cultural matters – within her own term of connotation and denotation – that has intrigued her. This fragment of representation through images of mask has been Dyan’s artistic expression for the last few years.

This particular preference is not a sudden-out-of-the-blue aesthetic output nor would it be something given. I assume it arises as a synthesis of these and anti-these channelled through artistic effort of an artist who has been creating her works in lengthy creative intensity and various aesthetic explorations. Supposedly, the particular methods of research have been done through observations and researches a la artist. Unlike a scientific approach that requires a scientist confined in a laboratory or quiet library, this method requires discussion, searching for photo reference, watching the mask dance and other ways. Therefore, the presented image has been a culminating point of her lengthy artistic evolution; a point in which she feel right to present the mask – both in connotation and denotation – as a representation of meaning trespassing the physical appearance of object itself. For Dyan, then, this particular image has been a proper illustration to visualize her world of idea.

Visually, when we observe her works closely, Dyan gives a careful attention toward form and images of mask itself. Through this, I presume, affective connaturality exists. Affective connaturality is a concept introduced by French philosophers Jacques and Raissa Maritain through their The Situation of Poetry: Four Essays on the Relations between Poetry, Mysticism, Magic and Knowledge, a book published in 1955. Though the concept itself derived from their critical approach toward literature, still, it is a relevant concept for recent context and could be adopted in evaluation of any form of artistic work, including visual art works. Affective connaturality is "correspondence between a subject and perceived object is not a relation between subject’s mind and perceived matter instead existed between object and subject’s interior leaning" [“korespondensi atau persangkut-pautan di antara seseorang atau seniman dengan apa yang diketahuinya tidaklah dilakukan oleh hubungan antara pikiran dengan obyek yang diamati, melainkan oleh hubungan antara obyek tersebut dengan perasaan dan kemampuan indrawi seniman/pengamatnya”].

This concept is represented within Dyan’s signature style – featuring various forms of mask – creating a distinct aesthetic identification. Her mask would be different from the works of Suwadji or other artists. This has occurred as she treats the object of her work not as “means of knowing” but rather as knowledge of instinct and inclination through the resonance within her self in creation of art work. Therefore the skilled creation of mask in various forms exists, a precise image of man behind the illustrated mask.

Then through her creativity, she placed the world of ideas within images of mask. Mask – once again – will emerge as apparatus, a sign that conveys her ideas. Thus appearance of masked figures is confronted with various social problems and dynamic intriguing for the artist. Numerous social and political matters has been addressed as subject matters of her canvass filled with opinion and interpretation for its viewer

A Self-critique

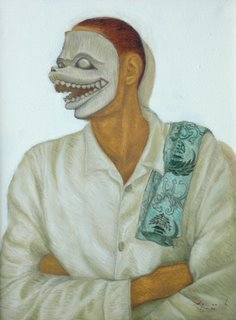

In this recent exhibition, for instance, we could find a quartet of works that possess a strong interpretation referring to the current condition of Korpri (Indonesian civil employee corps). This is an interesting representation due to the fact that Dyan is a civilian employee making her automatically a member of the corps. There is a masked man in white with piece of Korpri uniform seemingly as a tablecloth in his shoulder. While in her three other works, all men are featured bare breast with masks in various expressions. One is wearing Kopri-uniform-patterned tie, while other has similar uniform cloth wrap on his necks.

I think these works persuade interpretation toward the low working ethic of most allIndonesian civilian employees. They who are summed up to 4 millions people and responsible with all aspects of Indonesian government and bureaucracy are assumed – by Dyan – merely as servants, figures who failed to fit in civil servant system. With an extreme illustration of bare breast man with (korpri) tie, could we expect an adequate working system? Would they be able to work professionally as demanded by society accordingly to the changes in time?

This is Dyan’s crucial self-critique. As we all aware, the increasing amount of civilian employees during Soeharto’s regime in 1980s had its obvious preference on supporting the powerful within the red tape. They have been quadrupled in order to mobilize support toward the ruling party, Golkar, a significant pillar of Soeharto’s regime aside of Indonesian armed forces.

Therefore, after Soeharto regime – de jure – ended, its most “important” inheritance is excessive amount of civilian servants with vague job descriptions and relatively low working ethics. Underlying the fact that anyone who succeeded entering government bureaucracy would be assumed successful on making a vertical mobilization in his/her social status. And this has create problem as bureaucrats, civilian servants, possess an obsolete perspective that they are new feudal who demand service and appreciation on their newfound social strata instead of their works.

Then, it is true of what have been Dyan’s main attention as well as her “annoyance” in her works. They are man in disguise of their working status in order to profit a social recognition instead of doing the works within their capabilities. Those who are with their destructive priyayi (bureaucrat) and ningrat (aristocrat) mentality have been unproductive element of bureaucracy wasting millions of rupiahs per year. For a country in debt, this is a mega-irony. And Dyan – as part of the red tape and completely aware and experience such matter – would only comment and criticise through her works. Though it may not give positive impact in her working milieu, but I guess this kind of works able to inspire Dyan herself to reflect similar to President Franklin D. Roosevelt did, “don’t ask what your country could do for you but ask what you can do for your country”

Hence Dyan has heeded a warning on the growing social phenomenon in her works. Mask that has been an icon in Indonesian art and culture, in Dyan’s eyes, emerged in different meaning. Though it is not worlds apart or strikingly different, through her eyes, comical and lovely masks create such reading far from amusing or charming, even most likely filled with bitterness, irony and hypocrisy. Since, now, the mask has gone beyond its physical existence. It has produced a new meaning, altered from the previous one.

Are you wearing a mask right now? You should see yourself in Dyan’s works…

Kuss Indarto, Yogyakarta-based curator. You could drop him a line at kaprioke@yahoo.com

Translated by: vidhyasuri utami

Comments

dikasih shout box dong mas, biar mudah nyapanya :)